This section identifies and provides some detail about a variety of war experiences. Each aspect includes some initial information to support teachers and their students for engagement with more detailed integrated learning opportunities.

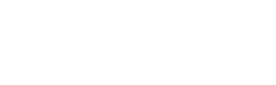

Image (right):

Patriotic song, Australia answers to the call

© By permission, State Library of NSW

Studio portrait of James Charles (Jim) Martin

©Public domain (AWM P00069.001)

During the First World War, the Australian Army's enlistment age was 21 years, or 18 years with the permission of a parent or guardian. Although boys aged 14 to 17 could enlist as buglers, trumpeters and musicians, many boys gave false ages in order to join as soldiers. Their numbers are impossible to determine.

Enlistment of boys was normal practice for the Navy and several died on service during the First World War. Five of those who qualify for the Memorial's Roll of Honour were serving on the Sydney-based training ship HMAS Tingira.

A 12-year-old Perth boy, Reginald Garth, stowed away on the transport RMS Mooltan. His three brothers and father had enlisted for the First World War and he wanted be part of what he thought would be an adventure.

Private James Charles 'Jim' Martin is the best known boy soldier. He is believed to be the youngest soldier on the Roll of Honour. James (Jim) was 14 years and 9 months when he died from typhoid contracted at Gallipoli. He had spent four hours in the water off Lemnos after the troop ship Southland that he was on was torpedoed heading to Gallipoli.

For further research: Boy soldiers on the Roll of Honour for the First World War.

Louise Mack, one of first women war correspondents.

©By permission, State Library of NSW

The withdrawal of about half a million men from the workforce did not result in their direct replacement by women during the First World War.

Women’s pay was less than men’s for the same work, sometimes as low as a quarter of a man’s wage. Unions were unwilling to let women join the workforce in traditional male areas as they feared that this would lower men's wages.

Women’s participation in the workforce rose from 24% in 1914 to 37% in 1918. The increase was in traditional areas of women’s work, with some increase in the clerical, shop assistant and teaching areas. Married women generally were not allowed to fill paid work positions.

The diaries of Miles Franklin describe her volunteer work during the war, typifying the actions of many women’s war effort. View Franklin's diary from January 1917 to February 1918.

The Government of the time also did not allow women to become more involved in war-related activities such as cooks, stretcher bearers, drivers, interpreters, munitions workers. This work did not occur until the Second World War.

Women were able to serve in the Australian army as nurses and other medical workers, but only if they were already trained and unmarried. They served in places such as Egypt, Lemnos, England, France, Belgium, Greece, Palestine and India. About 2150 nurses served overseas between 1914 and 1919. Many worked in military hospitals in Australia.

Twenty five nurses died and nearly 400 were decorated during the war. Seven women received the Military Medal, including four nurses — Alice Ross-King, Dorothy Cawood, Mary Jane Derrer, and Clare Deacon — for their actions on the night of 22 July 1917 when their field hospital was bombed.

Read a detailed account of the attack in the diary of Sister Alice Ross-King or in a transcript of King's diary.

Many nurses kept diaries, such as Sister Alice Kitchen who left Australia in the first convoy of nurses in 1914 and Anne Donnell who embarked for Europe in 1915. View Anne’s diary from 29 December 1917–31 January 1919 while in Ypres, France. A transcript is also available.

Access additional information about Great War nurses.

Links to ‘Nurses’ image gallery sources.

In recent times over 1300 Indigenous Australians have been verified as having fought in the First World War. Personnel records do not reference race or ethnicity other than the statement ‘natural born’ or the name of country of birth.

Indigenous men enlisted from the beginning of the war, despite a ruling technically banning them from doing so in 1914. As the war progressed enlistment did become easier as more and more recruits were required.

Once in the Army, a man became a soldier irrespective of the colour of his skin or country of birth, with no discrimination in pay rates. Soldiers forged friendships through their shared experiences, and survival in battle often came down to relying on your mates.

Some Indigenous men were decorated for outstanding actions. However, like most soldiers, they simply did what was necessary.

After the war, Indigenous veterans found that their war service counted for little, as discrimination remained or had worsened in areas such as education, employment and civil liberties. They were not given full citizenship rights and still had to live under the increasingly oppressive ‘Protection Acts’ that imposed strict control over their lives. They were also further displaced as the best farming land in Aboriginal reserves were confiscated for soldier settler blocks, to which they were not entitled.

In spite of this treatment, several Aboriginal families have a very significant history of service in the Armed Forces. This includes the Saunders and Lovett families.

Explore links to further information about Indigenous soldiers.

Horses were extensively used in the First World War. Australia sent over 136 000 horses for the war. Horses transported troops and carried or pulled ammunition, equipment and supplies. The Australian horses were known as Walers as they originally came from NSW. They were strong, resilient and able to survive with little water.

The 1st Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade organised into three regiments. In Gallipoli, due to the terrain, only a few horses were landed and so the 1st Light Horsemen fought on foot. Their horses were sent back to Alexandria for later deployment. Read more about the 1st Light Horse Brigade.

Due to quarantine regulations, the only horse to return to Australia was Major General William Bridges’ horse, Sandy. Although sent to Gallipoli he did not land and was transferred to France in March 1916. Read more about Sandy.

Dogs had several official roles in the First World War. Messenger dogs were attached to divisional signal companies and carried messages in a metal tube on their collar. Other dogs were trained to find explosives whilst others located injured soldiers. Mascot dogs were also often kept by troops to provide comfort and companionship.

Carrier pigeons played a crucial role in communication as they flew fast, were difficult to shoot down and their homing instincts meant they returned to their lofts, even if they had been moved. Pigeons carried messages in a metal tube attached to a leg band.

The Australian Army Veterinary Corps (AAVC) was formed in 1909 to care for the horses, in particular. Nineteen veterinary officers embarked with the first Australian Imperial Force contingent of 20 000 men and 7 500 horses.

Links to ‘Animals in war’ image gallery sources.

On the home front women were involved in a wide range of volunteer activities including fund raising and providing care packs for soldiers. Much of this was coordinated by the Australian Red Cross, a division of the British Red Cross. A number of women joined the overseas branches of the Red Cross to be nearer to loved ones or to provide nursing support in the field.

The actions of the Red Cross assisted to build community at a time of need and to provide tangible support for those fighting, injured and captured as prisoners of war. This support was a way for those at home to make a positive contribution to the war effort and to engage personally with those away at war.

The Red Cross was largely run and supported by women. The first Australian branch of the British Red Cross was formed in NSW by Mrs Langer Owner under the patronage of Lady Helen Munro-Ferguson. Within days of war being declared the Red Cross was setting up volunteer support networks. Initially the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) saw no role for a voluntary organisation. This changed in 1915 as the ill and wounded began returning to Australia where there was no support. The Red Cross provided comfort packs, transport, convalescent homes and rehabilitation support for the wounded.

View archival film clips, including Serving the troops at Screen Australia’s Red Cross Activities during and after WWI.

Links to ‘Red Cross’ image gallery sources.

Vera Deakin set up the Missing Enquiry Bureau, initially in Cairo, then moved to London and was helped there by Winifred Johnston. This bureau collected and recorded information about those wounded, missing, killed or captured and held as prisoners of war. This information was often sent back to families, at times arriving before official notifications. Many women volunteered for this work which also extended to include the Hospital Visiting Service.

The archival records of the Bureau are now held by the Red Cross. These records can be searched using Australian Red Cross Society, Red Cross Information Bureau, South Australia, WWI, and Prisoners of the First World War ICRC archives, part of the International Committee of the Red Cross Archives, Geneva.

The Australian Army provided men with very limited clothing and few comforts. Basics items including socks and warm clothing were sent over by a well organised network of volunteers. Jam, baked goods, musical instruments and Christmas parcels were just some of the additional items also provided by volunteer networks.

Volunteer support continued after the war for refugees, widows and children and the victims of war.

Links to ‘ACF’ image gallery sources.

On the home front there was strong community support for the troops fighting overseas. Women were encouraged to raise money, join voluntary organisations and make comfort items for the soldiers. These were coordinated by a large number of voluntary organisations including the Red Cross, Australian Comforts Fund, War Chest Fund and the Country Women’s Association. Comfort items included knitted socks, balaclavas, mittens and sheepskin vests.

School children were also encouraged to contribute to the home front and their efforts were publicised through school magazines and education gazettes. One school girl, thirteen year old Ruby Wallace from Edinglassie Provisional School, knitted 237 articles, including 100 pairs of socks.

Further information: Patriotic Fundraising in NSW, Public School Children Help Out and Australians in World War I: Home Front.

Links to ‘Home front’ image gallery sources.