Overview

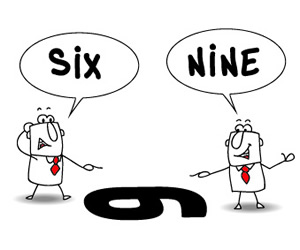

What’s happening in the image? Could you draw your own picture of a similar scenario?

Have you ever seen something from a certain perspective but discovered others have a completely different view? What affects how you and other people look at things? How do storytellers create a true story using different texts?

Using personal stories, this project looks at how the way we see something is influenced by both our own perspectives as we are responding, and by the perspective of the person composing.

You will explore the techniques composers use to create a point of view and how narratives can be used to represent people.

Then it’s your turn. With a group, you’ll collaboratively compose and publish a true story using online tools. Suggestions for tools to use are made throughout the project.

When you have finished working through this learning activity we would like your feedback so we can improve it. Please complete this short survey.

Get organised

Work in a collaborative group as you make decisions, problem-solve, give feedback and create. Four members is an ideal group size.

Collaboration is effective when each team member is responsible for part of the task that the group relies on. It also works best when team members work together to create the final product, in this case, a personal story.

How do you do both these things? Breaking this into effective talk and team roles can help.

To make conversations fair, respectful and useful, it's good to develop some guidelines around how you talk and listen to each other.

Brainstorming ideas, making decisions together and resolving differences of opinion will need a range of conversation skills.

Use the suggestions below and add to them to come up with guidelines for good collaborative conversations.

-

stay focussed

-

ask questions

-

everyone gets a turn

-

make connections

-

listen carefully

-

clarify meaning.

As you work through Truth be told each team member will have different roles depending on the different tasks.

Upload the team roles template (.docx 31kB) to Office 365 or Google Apps to organise the roles for each member of your group. Share the document to all group members and update it if needed. View the team roles example (.docx 121kB) for more ideas.

One of the most important roles in a collaborative project is the ‘host’. This student will set up a shared folder with all the documents and share them with their group.

What documents, either provided in this resource or those you create or find yourself, will need to be organised and shared with the team?

|

|

Discover

Use the information here to build your understanding of truth and perspective and engage with a range of ‘true’ stories.

What choices does a composer make as they represent a person, character or event?

Representations are not neutral - composers make many choices either consciously or unconsciously, depending on their perspective. It is through perspective - and the values contained in that perspective - that we think about a text one way or another.

Another factor that influences how we engage with a text is the context it was made in (the composer's) and the context it is experienced in (the responder's).

As responders we want to ask ourselves, how am I being positioned in this text? Considering the answer to this question can also help us decide whether we think something is true or not.

After watching the video The lab: Decoy – a portrait session with a twist discuss:

-

How are the photographers influenced by their idea of the model’s background or life story?

-

How could a photographer (composer) be objective?

-

How much is a viewer (responder) influenced by their idea of the model’s background or life story?

Your teacher may need to access this video on YouTube.

One way to understand the differences between fiction and non-fiction texts is to discuss genre - groups of texts with similar forms and functions.

Many factors contribute to genre, including codes and conventions - patterns of sounds, spelling, grammar, tone of voice and paragraph structure, to name a few.

What is different in a fictional story and a non-fiction story? What about fictional accounts based on real events?

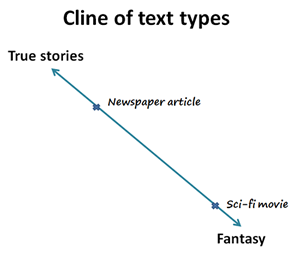

In your group, create a cline with true stories (non-fiction) at the top and fantasy (fiction) at the bottom. Include as many types of texts as you can on your cline. Discuss your decisions with another group or present to the whole class.

Use your completed cline to describe the codes and conventions, and other features that make up the two genres, of true stories and fictional texts.

-

Create a graphic organiser such as a T-chart or Venn diagram to compare and contrast each genre - True Stories and Fiction. Use your chosen software tool to record your ideas

-

Feed back your ideas to your class

-

Review your group diagram after listening to other groups.

|

|

What are true stories and how best can we tell them?

Here you will investigate what a true story is and the different media a true story can be told in. How does each medium engage you?

Explore true stories by looking at narrative, a genre composers use to organise and shape life experiences. Narratives express our ideas and values.

Explore what you think a true story is using this process:

-

Think - what do you personally think?

-

Pair - share your definition with another person.

-

Share - present your definition to your class.

Capture and save a class definition.

Different media use a range of points of view to tell a story. Explore a variety of texts in Creating digital and multimodal texts.

Use this text analysis matrix (.docx 127kB), or create your own, to help you identify the various devices used in different texts.

For example:

-

visual texts use devices such as foregrounding or backgrounding and size

-

written texts use devices such as narrative stance - omniscient, first, second or third person

-

film uses devices such as camera angle and soundtrack.

In this section your class will analyse a text, looking for the points of view the composer has used. Use the matrix to support your analysis.

Consider how you responded to the text studied.

-

How did the composer try to engage you in the story? What points of view did they use?

-

What moved you as you engaged with the story? What complications or conflicts interested you?

Share with the class or a group. Capture and save the top five features that can make a story engaging to responders.

|

|

Now you can dive in to a story with your team.

Your group will:

-

choose a story to analyse from the list below

-

identify the different points of view each composer has used, using the matrix as a guide. Consider splitting the task so that each team member is working on one or two different components of the same story.

-

discuss the questions below the story you study

-

put all your work together so that, as a group, you can give a full analysis of that story

-

create a page in a document that is shared with other groups (see the suggested tools below) to capture your group’s response

-

present your analysis on your story to the whole class.

Your teacher may provide other stories also.

|

|

Your teacher will show you a YouTube film made by a student in Queensland about her family’s battles with drought on their farm – Ellen’s Story.

Task: Watch the entire documentary. View it again, this time focusing on these questions:

-

what different camera angles are used and how do they help tell the story?

-

how does the music affect you as you watch the film?

-

why does Ellen use a map and text to help tell her story?

-

how does your knowledge of drought affect your perspective of the story?

-

has that perspective changed now that you’ve watched it?

This program is part of Radio National’s ‘Conversations with Richard Fidler’ series, produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Stan Grant’s long road to recognition

Task: Listen to the entire interview. Listen again, this time to an excerpt (say, 01:54 - 7:30) and consider these points:

-

what role does the interviewer play in drawing out Stan Grant's story?

-

how did what you already know about Stan Grant affect your perspective of the interview? Did your perspective about him change afterwards? How?

-

how does the medium (audio with one still image) help you engage with this personal story?

-

what are the differences between a person telling their own story and someone else telling it for them?

-

how might Stan Grant's story differ if he had written it down instead of speaking it?

This magazine article is part of a series in The Sydney Morning Herald Good Weekend magazine.

Two of us: Lucas Patchett and Nicholas Marchesi

Task: Annotate a copy of the article focusing on:

-

what do you notice about the language and tone of this article?

-

how are you as responder drawn into the story?

-

how does the writer encourage you to react to the characters?

-

how does the perspective both people have on each other and the same events affect your perspective of them?

This Adobe Slate was created by a NSW student, Brooke Fenton. It tells the story of a woman called Karina Sole who lives her life with serious kidney disease.

Every day is a good day – Karina Sole

Task: Navigate through the Slate. Read it again, this time analysing the story using these questions:

-

do you know anyone facing serious health issues? How does that affect your perspective of this story? Did your perspective change after viewing the video?

-

what role do the images play in telling this story?

-

why do you think the composer did not use a voice-over?

-

what role does the text play in this story? Why are different fonts used?

Childhood memories help lay Holocaust survivor to rest after 23 years

Task: Create an inverted pyramid to show the structure of a news story. (Fill in the sections to show the who, what, when, where, why components.)

Save your notes.

-

what do you notice about the language used?

-

comment on the use of adjectives and how they help build the story.

-

how is this news story different to a typical 'news breaking' story?

-

why is a story like this considered newsworthy?

This program was produced by the Witness radio program, British Broadcasting Corporation World Service.

The world’s most valuable T-Rex

Task: Listen to the program. Listen again, this time considering:

-

how many people are involved in the story?

-

how are different perspectives treated?

-

create a Y-chart for context, tone and language and fill in the features.

-

share your feedback with the class through a structured brainstorm.

Create

Whose truth will you tell?

Now you’re ready to write a personal story and try to convince your group to produce it.

As part of this process you will give and get feedback, and revise your work to improve it.

Finally your group will decide which story to work on together.

-

Write your own true story using your knowledge about the features of non-fiction texts. Your story could be about you, a friend, a family member, someone in your community or someone you’ve heard about who interests you.

-

Think about what medium you will use to tell your story. Could it be a movie, an audio story, a photo story with text?

-

Share your story with your group.

-

Discuss each person's story and give constructive feedback. Make sure you:

-

ask questions about the story

-

point out things you like

-

offer suggestions for how the story could be improved.

-

-

Use the feedback to improve your story.

|

|

It’s time to pitch your improved story to your group and persuade them that yours is the best one to work on.

Use The Pitch - Sell your idea to help scaffold your mini presentation.

Presenting your pitch:

-

focus on why it would be the top story to produce - you have up to 90 seconds

-

outline why an audience would be interested in this story

-

pose a puzzle to attract attention to your story

-

explain what medium you are proposing and why

-

share your passion and enthusiasm about your idea.

|

|

Decide with your group which story you will create and publish.

Use the Decision-making criteria (.docx 121kB) to help scaffold your discussion.

As part of this process you can start to make decisions about who will do what roles as you research, draft, review and publish your story.

|

|

Culminating task

Now that you have decided on the personal story to tell and the medium to use, your team needs to collaborate to produce a story you are all proud of.

Consider:

-

what other aspects of the story could be added?

-

what further research needs to be done?

-

what roles are needed now that you have moved into the publishing phase?

-

what equipment or resources will you need?

Revisit your notes (in Read, view, listen) about the features of the medium you have used to tell the story. See Technology rubrics for any classroom for advice about your chosen medium.

Work in your groups to create a draft and share it with your teacher and other peers for feedback.

As you give feedback think about whether the story fits the title of this project – has the truth been told?

|

|

Review your story using any feedback to make changes.

Now you are ready to publish and share with a wider audience.

Your group or class could:

-

host a showcase event for a school audience, parents and wider community

-

share class stories together on a blog like Humans of New York

-

upload your story to a platform like YouTube.

|

|

Reflection

Reflect on your learning using the questions below.

True personal stories:

-

What have you learned about perspective?

-

What have you learned about the power of narrative to tell the truth?

-

What was your favourite medium for telling a personal story? Why?

-

Was the story you worked on an example of ‘truth be told’? Why?

Collaboration:

-

As a group, reflect on what worked well and what was challenging as you worked together throughout this project.

-

As an individual:

-

Name the best thing about collaborating with others to produce one story.

-

Name the most challenging thing about collaborating with others to produce one story.

-

What did you learn about yourself as you worked with peers?

-

|

|

Information for teachers

This resource supports student-centred, project-based collaborative learning using Google Apps for Education, Office 365 and other online tools.

|

|

The toolbox icon highlights that a software tool could be used for this activity. Select the adjacent hyperlink to see suggestions of suitable tools to use, or choose your own. |

This resource supports students in the following English K-10 syllabus Stage 5 outcomes:

A student:

-

effectively uses and critically assesses a wide range of processes, skills, strategies and knowledge for responding to and composing a wide range of texts in different media and technologies EN5-2A

-

understands and evaluates the diverse ways texts can represent personal and public worlds EN5-7D

-

purposefully reflects on, assesses and adapts their individual and collaborative skills with increasing independence and effectiveness EN5-9E.

Truth be told supports the English textual concepts:

-

code and convention

-

context

-

genre

-

narrative

-

perspective

-

point of view

-

representation.

See English textual concepts descriptors and summaries for an explanation of each textual concept and why it is important. Stage descriptors for each concept are included.

Visit Process descriptors and summaries for key aspects of English processes. Stage descriptors for each process are also listed:

-

understanding

-

engaging personally

-

connecting

-

engaging critically

-

experimenting

-

reflecting.

Truth be told provides explicit pathways for learning across the curriculum content for the following:

-

cross-curriculum priorities:

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures

-

-

general capabilities:

-

critical and creative thinking

-

ethical understanding

-

information and communication capability

-

intercultural understanding

-

literacy.

-

Where students choose an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person as the subject of their story, they may use the following wording where appropriate:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that this resource may contain images and voices of people who are since deceased.

Ensure that students practice good digital citizenship by providing correct attribution and copyright information for images.

Useful links:

Consider how and when you and your students will give feedback, and formative and summative and assessment at different points throughout the project.

Online collaboration tools can provide a range of feedback and assessment methods.

Consider using:

-

the comment tool in Google Docs or Word Online to give specific feedback at a particular point

-

the simultaneous audio and written commenting functionality in OneNote Class Notebook

-

other programs – for example Jing, Screencast.com – to give feedback via screencasts and audio.

See Technology rubrics for any classroom for marking guidelines for digital work.

The YouTube videos below used in this resource may not be available to all students.

Discover section – Truth and perspective

Discover section – Read, view, listen

21st century learning design (21CLD)

This project targets 21st century learning skills including:

-

collaboration — do learners make substantive decisions together? Is their work interdependent?

Students will work collaboratively to decide:-

what roles are needed and who will fill them

-

how roles will change over the project

-

which story to produce

-

how to create a story in the chosen medium which draws on the work of the whole team.

-

-

knowledge construction — do learners make connections and identify patterns? Do they apply their new knowledge to new contexts?

Students will construct knowledge as they:-

identify the features of different types of texts

-

use their knowledge of true stories and different media to produce their own stories

-

use their knowledge of how composers engage responders to produce an engaging story.

-

-

skilful communication — do learners produce substantive, multimodal communication? Do they reflect on the process of learning to improve their communication?

Students will communicate skilfully as they:-

give feedback to peers about their work

-

reflect on feedback to improve their work

-

try to persuade peers to choose their own story for production

-

use multimodal forms of communication to organise and create their group projects.

-

See 21st century learning design for more information.

These notes provide additional information to support teachers as they guide students through each section of this resource.

This section aims to engage student interest in the project and activate any prior knowledge. Use the cartoon and questions to provoke discussion about the big ideas in this resource.

The overview also broadly outlines the learning students will be doing and what they are expected to produce by the end of this project.

Skills in collaborative work are critical to this learning activity. Organising the tasks and their roles throughout the project will provide students with opportunities to develop their 21st century learning skills.

Forming groups — teachers will make decisions about suitable group selection processes based on their knowledge of their class. One option is for students to pitch their stories to the class and choose the team they wish to work with.

Four members is an ideal group size.

Effective talk — what prior teaching will students need around group discussions to make them effective and authentic for every group member? Students can use the points provided to create their own guidelines around what makes for productive and respectful collaborative talk. What will they do if differing opinions can't be resolved?

Team roles — how will students document their changing roles over the course of their project? Using online tools to record information means it can be referred to at any time over the project. What will they do if individual responsibilities are not followed?

Learn more about assigning Student roles.

Online collaboration

Students can set up a shared Google Drive or Office 365 OneDrive folder accessed via their Student Portal landing page. One team member does this and shares the folder with the others. Ensure each group shares the folder with the teacher so you can monitor progress and support students as needed.

Having a space to share folders and files will assist students to work collaboratively. Students can contribute simultaneously to shared folders and documents, enabling the responsibility and work, including writing tasks, to be shared. Groups can continue working even when one or more members are away. Students can work on tasks out of class time.

After completing the Get organised section students should have created a shared workspace that contains:

-

discussion guidelines

-

roles and responsibilities documents.

As work progresses, other documents — either created by the students or provided in this resource — will be added to the shared group space. These include a:

-

cline of text types

-

graphic organiser that compares and contrasts true stories and fiction

-

definition of a true story

-

text analysis matrix

-

mind-map of what features make a true story engaging

-

decision-making criteria

-

draft and final version of group story

-

group reflection on the collaborative process.

These documents could possibly be organised into folders using the section headings of this resource.

This section contains activities which aim to:

-

trigger student prior knowledge

-

build new understandings that students can apply when they create their own story

-

provide opportunities for students to develop their 21st century learning skills.

Truth and perspective — show the YouTube video The lab: Decoy - A portrait session with a twist. Students are able to watch the video at home. Hold a class discussion after viewing using the questions provided as a stimulus, or create your own.

Fiction vs fact — the activities in this section build student understanding of genre, codes and conventions, and the differences between factual and fictional texts.

Telling true stories — if you think it necessary, do a whole-class joint analysis of a personal story your students might be familiar with, before they have to analyse texts in their group. Highlight how the composer has used points of view to position the responder. Consider how those points of view engage responders.

How can they be told? — this could be a paired task or done in groups.

Read, view, listen aims to:

-

expose students to a variety of texts telling personal narratives

-

build knowledge of various media using the English textual concepts as a framework

-

highlight gaps in student knowledge, thus providing teaching points needing explicit instruction

-

allow students to practice collaboration within groups and across the class.

Students can use the provided matrix to help analyse the texts. Adapt and use this matrix according to the needs of your students - some will complete missing sections, others may use a highlighter to mark features they identify.

Each group is responsible for one story from the list provided, or choose your own texts. When compiled, each group analysis will become a class resource students can refer to. Ensure each of the texts is covered by at least one group.

Show the YouTube video Ellen Gett’s drought documentary – Ellen’s story. Hold a class discussion after viewing using the questions provided as a stimulus, or devise your own.

Stan Grant’s long road to recognition and The world’s most valuable T-Rex—download the audio files from the websites if necessary.

Peer feedback is a significant part of this section. Consider if you as the teacher will also give feedback to students. How and when will you give it?

How and when will you give feedback to your students? Will the feedback enable them to make changes before finalising their work?

Decide as a class how the final stories can be showcased to a wider audience.

Reflecting on the learning content and the learning process is a critical part of 21st century education.

Use the questions provided or devise your own.

Follow your regular reflection or journaling routines or guide students to use online tools to capture their thoughts.

As the teacher you also may like reflect on how you might improve on the delivery of this project. What have you learned about embedding 21st century skills into a learning experience?

This resource has been developed by a collaborative team of writers to support the department's Rural and Remote Blueprint for Action.

Collaborators:

-

Carla Saunders, head teacher English, MacIntyre High School, Inverell

-

Judith Noad, English teacher, MacIntyre High School, Inverell

-

Diana Goodfellow, curriculum advisor, Educational Services, Coffs Harbour

-

Prue Greene, English Advisor K-12, Secondary Curriculum, Learning and Teaching Directorate, Sydney

-

Penny Galloway, learning design officer, Learning Systems Directorate, Sydney.

Educators are encouraged to write their own Collaboratus resource and share with colleagues.

For more information see the Collaboratus: resource model and look for the Collaboratus template in Google Sites (DoE only).